October 31 approaches, the official five hundredth anniversary of the Protestant Reformation. No doubt Halloween will prove interesting this year, as surely we must all dress as our favorite Reformers. Based on a cursory internet search, however, I note that no one has yet seen the Reformation costume market as the lucrative business opportunity it might be—all profits to good causes, naturally, although such business-based benevolence would by no means count as good works toward salvation.

If you prefer some other strategy to commemorate this anniversary season, publishers have your needs well in hand, with numerous Reformation-related titles released this year. Or you might join the throngs of travelers making pilgrimages to Reformation-related sites in Germany and Switzerland, thereby testing the limits of the hospitality industry’s resources. (Another genius business idea: Luther-themed porta potties to ease the needs of the pilgrim crowds. Brand name: “Tower Experience.”)

To begin my own commemoration, this week I attended the opening—it seems un-Protestant to describe it as a “gala” opening—of an art exhibit at Calvin College titled “Stirring the World: German Printmaking in the Age of Luther.” While prints made from woodcuts and engravings may not offer the immediate thrill of gigantic oil paintings, they do display curious combinations of grotesquerie and piety and, to the patient observer, a fascinating glimpse into the Reformation moment.

The title of the exhibit comes from the words of a Dutch fellow, Karel van Mander, who wrote disdainfully in 1604 that the upstart monk Luther, with his 95 Theses and other polemical writings, “had begun to stir the quiet world.” That’s silly, of course. There was nothing quiet about the world in 1517.

In fact, prints of the period demonstrate vividly that Luther and his contemporaries expected the apocalypse any minute. Why not? A horrendously corrupt church establishment, diseases and plagues, astrological and meteorological weirdness, witches, Ottoman Turks, class unrest, and all these technological and political upheavals! How could the world survive? Better to repent and get ready.

Poor dears. They had never even heard of nuclear missiles or climate change.

In an essay on apocalyptic art in the exhibition book, Robin Barnes notes that when Luther entered the European scene with his calls for ecclesiastical reform, the “atmosphere was already heavy with queasy forebodings.” We can see those forebodings in images like Albrecht Dürer’s famous “Four Horsemen” as well as in many others featuring monsters, witches, distortions, debaucheries, and that ultimate indicator of divine judgment: hailstorms.

In an essay on apocalyptic art in the exhibition book, Robin Barnes notes that when Luther entered the European scene with his calls for ecclesiastical reform, the “atmosphere was already heavy with queasy forebodings.” We can see those forebodings in images like Albrecht Dürer’s famous “Four Horsemen” as well as in many others featuring monsters, witches, distortions, debaucheries, and that ultimate indicator of divine judgment: hailstorms.

Printers, admittedly, made use of these terrifying images to pump up book sales, but that doesn’t mean people weren’t truly afraid. God and the devil had been in conflict since Eve plucked the apple, and the battle was obviously reaching some sort of climax. Barnes remarks, “Luther saw his own movement to revive the gospel as the last act in this great conflict.”

Thus, Luther did not imagine he was awakening the dawn of a new, more enlightened age. He and his compatriots in those early years were more like the prophets running for the hills while yelling over their shoulder “Repent! The end is near!” In his lecture on the exhibit, my colleague Henry Luttikhuizen assured us that there are exhibitions elsewhere featuring the “nice” Luther, the more mature, pastoral Luther who comforted his flocks. Our exhibition dwells upon the anxieties, fears, and agitation of Luther’s day and age.

Evidently, the apocalyptic panic of the early sixteenth century eased up a little as the years passed and the movement began to focus on building institutions from the ground up. John Calvin was slightly less likely to glance up from his study on rainy days wondering if he was beholding the first drip-drops of another world-ending flood. Nevertheless, as Henry observed wryly, “being Reformed has always involved a certain amount of agitation and dissatisfaction.”

I suppose I was carrying contemporary agitation and dissatisfaction with me as I viewed the prints, beautifully exhibited in the Calvin Center Art Gallery. The work of several artists is featured, but my favorites were all by Albrecht Dürer, who, though he remained Catholic, greatly admired Luther and was connected to him through mutual friends.

In three prints that especially drew my attention, I noted the ominous presence of an hourglass. In Dürer’s famous depiction of personified melancholy, “Melencholia I,” the hourglass is positioned above the head of the moping figure: time is literally hanging over her head. Melancholy was thought to accompany genius, Henry explained in the lecture, since one of the terrible burdens of genius is knowing that your time to crank out genius-derived works is inevitably limited.

In three prints that especially drew my attention, I noted the ominous presence of an hourglass. In Dürer’s famous depiction of personified melancholy, “Melencholia I,” the hourglass is positioned above the head of the moping figure: time is literally hanging over her head. Melancholy was thought to accompany genius, Henry explained in the lecture, since one of the terrible burdens of genius is knowing that your time to crank out genius-derived works is inevitably limited.

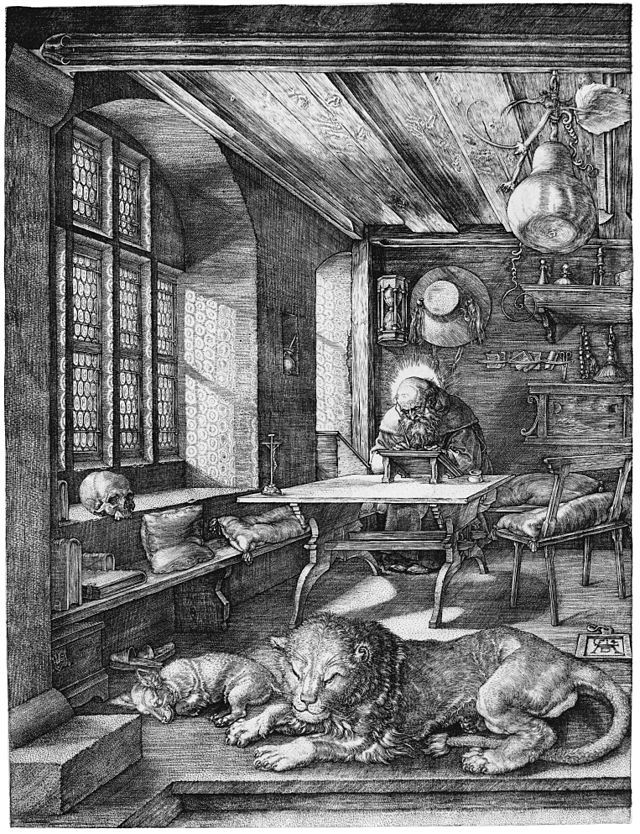

Another work, “Knight, Death, and the Devil,” places an hourglass in the hand of a ghoulish death figure, plodding along beside a stalwart knight who gazes stoically ahead. In the serene “St. Jerome in His Study,” an hourglass hangs behind Jerome’s head as he works intently at his study table, a tame lion and content dog lounging in the foreground.

Those hourglasses provoked a response in me because, I imagine, in every age we feel that time is fearfully short. Especially those of us deep into middle age or beyond: we wonder how much time we personally have left. And what is the world coming to anyway? Floods and hurricanes, political trauma, genetic experimentation, tech advances moving so fast it’s all a blur. I’ve found myself musing about potential grandchildren and wondering if I should gently advise my children not to feel obliged. What’s the point when the End of All Things is obviously so near?

Dürer’s prints seem to underscore and respond to all this queasy foreboding. Time is always running out, these works suggest, so perhaps you should train your eye on something else. Maybe moping old Melancholy isn’t quite the right model, but that knight seems to be marching right along, refusing to let Death and the Devil get to him. In fact, his horse might just crush that random skull on its next step forward. And Jerome, with his halo looking as if scholarly work has set his head on fire, has a skull set up on the window sill as a constant memento mori. But if he were to raise his eyes from the Word to gaze upon that skull, his view would be blocked by the crucifix positioned on the corner of his desk.

Dürer’s prints seem to underscore and respond to all this queasy foreboding. Time is always running out, these works suggest, so perhaps you should train your eye on something else. Maybe moping old Melancholy isn’t quite the right model, but that knight seems to be marching right along, refusing to let Death and the Devil get to him. In fact, his horse might just crush that random skull on its next step forward. And Jerome, with his halo looking as if scholarly work has set his head on fire, has a skull set up on the window sill as a constant memento mori. But if he were to raise his eyes from the Word to gaze upon that skull, his view would be blocked by the crucifix positioned on the corner of his desk.

I think the idea is that it matters where you set your sights. As the writer of Hebrews might say, “Let us fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy set before Him endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:2).

In the end, I found these prints, and this whole exhibition, oddly comforting. Maybe the world is always ending. Maybe fear and upheaval are always part of the deal. Maybe what seems like an end can become the beginning of a new age, should God extend sustaining mercy a little longer. If our pious forebearers, in despair about corruption and disaster, could keep their eyes on the cross, well then so can we.

The exhibit at Calvin College is free and open to the public until October 14. Little magnifying glasses are kindly provided to enhance viewing enjoyment of these intricately detailed works.

Fun bonus fact: Around 1580, Luther fan Wolfgang Stuber adapted Dürer’s Jerome work, putting Luther at the study table instead of Jerome. Still with the hourglass, but no halo, and no cross between Luther and the skull. Hunh.