Over the years, during many a frigid January in Michigan, while dragging out of bed in the winter darkness to teach a three-hour-a-day interim course at Calvin, I’ve created my fondest January fantasy: hole up in a woodsy cabin with my husband and read books. “Thirty days, thirty books,” I call it. I know: that is one hopelessly nerdy dream.

Well, this year, thanks to a sabbatical, I am doing my best to make my dreams come true. I’m at home, not in a cabin, and my husband is traveling, not with me. But I’ve still got books, and lots of ‘em. The guiding question for my reading is this: how will our spirituality (and our churches) need to change in order to survive the unprecedented challenges ahead, particularly the climate crisis? Here’s what I’m learning so far.

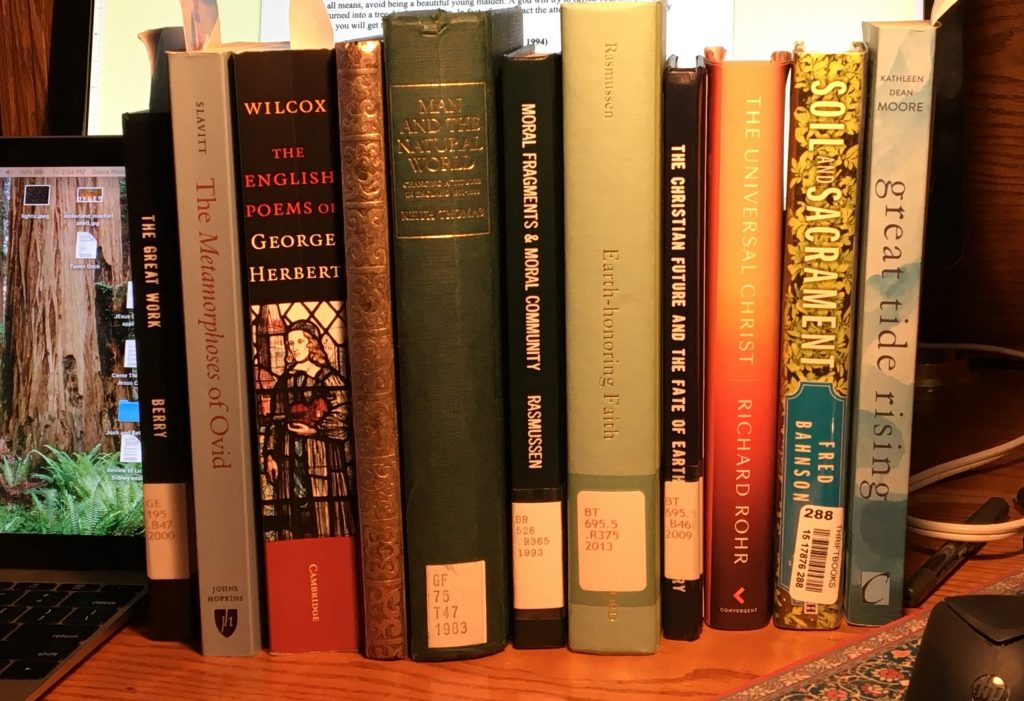

Thomas Berry, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future (Three Rivers, 1999)

Berry’s many books get quoted all the time among nature writers, ecologists, and theologians, so I wanted to read him for myself. He’s your view-from-thirty-thousand-feet guy: mystical, philosophical, thinks in terms of the entire sweep of cosmic history. Raised Catholic, PhD in history, taught at Fordham. Called himself a “geologian” (died in 2009).

We’re in the midst of giant transition, writes Berry. For millennia, we worked on divine-human relations, then we worked on human-human relations. Now we need to work on earth-human relations: “[W]e need to understand how the human community and the living forms of Earth might now become a life-giving presence to each other.”

This is the Great Work before us, and it ain’t gonna be easy: “Our own special role, which we will hand on to our children, is that of managing the arduous transition from the terminal Cenozoic to the Emerging Ecozoic Era, the period when humans will be present to the planet as participating members of the comprehensive Earth community.”

So what do we do? Well, repair our notions of radical discontinuity between humans and the universe. Reconcile our practical alienation. Use all the forms of wisdom we have, including religion and science. One nice thing about Berry is that, while he certainly deplores human abuse of the planet, he also offers appropriate huzzahs for culture, civilization, art, etc. That’s all part of our evolution toward a higher consciousness, he says.

Berry is among the “universe is evolving toward consciousness” kind of thinkers. I find him at times profoundly wise and visionary, and at times frustratingly whooshy. One has to contend with sentences like this: “When we speak of the natural world we are not speaking simply of the physical world but of the psychic-physical mode of being found in every articulated entity of the phenomenal world.” Uh. OK. But then he’ll come up with a zinger like this: “after these centuries of industrial efforts to create a wonderworld we are in fact creating a wasteworld.”

Pope Francis, Laudato Sí

Speaking of critiquing the military-industrial-commercial-extractive complex, the Pope’s encyclical is a remarkably frank document: “The earth, our home, is beginning to look more like an immense pile of filth.” He spares no critique of our “deified market” and ruthless exploitation of the earth and of people.

Like many writers in this genre, Pope Francis affirms the inherent value of all creation and deplores our indifference and abuse: “It is not enough … to think of different species merely as potential ‘resources’ to be exploited, while overlooking the fact that they have value in themselves.” Because of our selfishness and foolishness, “thousands of species will no longer give glory to God by their very existence, nor convey their message to us. We have no such right.”

The remedy here, as in Berry, is the repair of our arrogance and resulting alienation: “if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously.” As a Calvinist, I doubt it, but it’s worth a try.

The Pope is admirably clear, as has often been noted, on the connection between justice for the poor and care for the earth: “Today … we have to realize that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach; it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.”

I was surprised to see how much the Pope’s words resonate—in more explicitly Christian language—with Thomas Berry’s. Here’s a lovely statement, for example, that resonates with Berry’s concept of mutual presence: “Rather than a problem to be solved, the world is a joyful mystery to be contemplated with gladness and praise.” And “The ultimate purpose of other creatures is not to be found in us. Rather, all creatures are moving forward with us and through us towards a common point of arrival, which is God, in that transcendent fullness where the risen Christ embraces and illumines all things.”

Also like Berry, the Pope is keenly aware that we have reached a hinge point in history: “Although the post-industrial period may well be remembered as one of the most irresponsible in history, nonetheless there is reason to hope that humanity at the dawn of the twenty-first century will be remembered for having generously shouldered its grave responsibilities.”

Richard Rohr, The Universal Christ: How a Forgotten Reality Can Change Everything We See, Hope For, and Believe (Convergent, 2019)

One more Catholic writer. Rohr’s subtitle is maybe a little ambitious? But he is drawing from his fifty-plus years as a priest, scholar, and world-wide explorer of human spirituality in order to push us from our reductive and brittle views of Jesus toward a renewed communion with the cosmic Christ.

Rohr is usually very generous with all branches of the Christian faith, though he’s not afraid to critique them, either, including his own Catholicism. I found quite satisfying his scathing critique of Protestant obsession with penal substitutionary atonement. He places this view of atonement in historical context (it’s only one relatively recent view), then writes: “At best, the theory of substitutionary atonement has inoculated us against the true effects of the Gospel, causing us to largely ‘thank’ Jesus instead of honestly imitating him. At worst, it led us to see God as a cold, brutal figure, who demands acts of violence before God can love his own creation.”

The benefit of retrieving the cosmic Christ of John 1, Colossians 1, Romans 8, etc., is that it makes much better sense of how the universe figures into the whole plan of redemption. For me, it also helps illuminate the particular continuity between the earthly Jesus and the Christ I now try to meet in my daily life.

As for the challenge of how to rehabilitate our notions of atonement, I think Rohr handles it pretty well by turning to his abiding concern with deep transformation. “Even God has to use love and suffering to teach you all the lessons that really matter. They are his primary tools for human transformation.” (Rohr really likes italics. And exclamation points.)

H. Paul Santmire, Nature Reborn: The Ecological and Cosmic Promise of Christian Theology (Fortress, 2000)

And now, a Lutheran. Santmire is terrific: clear, organized, nuanced. Puts many other thinkers into perspective. His question in this book: Does Christianity have anything useful to say in the midst of the climate crisis? Or are we the bad guys? His answer: Yes, Christianity does have something useful to say, but we have to “revise the classical Christian story to identify and to celebrate its ecological and its cosmic promise.”

He works through critiques and appreciations of Matthew Fox, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Martin Buber, and others. He, too, advocates emphasis on the cosmic Christ, while warning against getting too whooshy about evil and sin. The real problem is not the concept of original sin, he says, “The real problem is rather the finally undeniable reality of radical evil itself, to which the doctrine of original sin, in various ways, has historically—and sometimes inadequately—borne witness.”

Christus Exemplar is well and good, that is to say, but we also need Christus Victor and Christus Victim. “Otherwise we will end up with a so-called savior whose salvation is commensurate neither with the powers of evil nor with our alienation from God.”

Santmire offers some appreciative quotes from Calvin as well as an extended, learned, philosophical, and surprisingly useful consideration about whether we can commune with a tree. Spoiler: yes, but we need new categories of being, and we should devise some.

Like the Pope and Rohr, he also includes a moving passage on the beauty and meaning of the Eucharist.

To sum up these four works, then:

Alienation from the rest of creation: must fix.

St Francis is a hero. So is Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

Indigenous peoples have gotten a lot right. We need to listen to them.

Descartes is a bad guy.

We need to adjust our theology/practice to focus on the Cosmic Christ.

Private ownership has caused a lot of problems. It’s necessary but we need to rethink it.

Eucharist = good.

We’re going to need to face limits and redefine progress.

And now, a few hot takes on some other books I’ve read this month:

Keith Thomas, Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500-1800 (Allen Lane, 1983)

Chock full of quotes from primary sources. Turns out people have always had a lot of ideas about the relationship between “man” and “nature”: “It is difficult nowadays to recapture the breathtaking anthropocentric spirit in which Tudor and Stuart preachers interpreted the biblical story.”

HOWEVER, “By 1800 the confident anthropocentrism of Tudor England had given way to an altogether more confused state of mind.”

In the meantime, the rise of natural history, much hand-wringing about how we treat animals, plants, and land, the romanticizing of nature and pets, a fern craze, and the end of bear-baiting.

Ovid, The Metamorphoses of Ovid, Trans. David R. Slavitt (Johns Hopkins UP, 1994)

By all means, avoid being a beautiful young maiden. A god will try to ravish you, and then you will get turned into a tree, bird, or fountain. In fact, if you attract the attention of the gods in any way at all, you will get turned into something.

Laurie King, The Beekeeper’s Apprentice (St Martin’s, 1994)

Sherlock Holmes did not retire; he took up residence in the countryside and then acquired, by accident, a feisty young gal who became his apprentice and then wrote numerous detailed accounts of their murder-and-crime-solving adventures as mutually respectful partners. There are fifteen novels, and since my library didn’t have #2, I skipped to #3 only to discover that in book 2, oh dear! No, I shouldn’t give it away…

Owner’s Manual, Kenmore Microwave model 72180043700 (online)

This has been perhaps my most informative read so far. Did you know that you’re supposed to clean frequently and eventually replace the grease filters underneath the micro in the hood part? And not just leave them alone for ten full years? So that explains the horrid grease spot on my ceiling…