Willemtje Hoogvliet was born in 1785 in Nieuw-Beijerland, South Holland, the Netherlands. She grew up, married Leendert Arendse, and at age 28 in 1813, had a daughter. By then, both Willemtje’s parents were dead. Then Leendert died a year later in 1814. In 1816, Willemtje had another child. She named him Jan Hoogvliet—using her maiden name. The birth record for Jan simply says, “mother has been widowed two years.”

Willemtje, honey: what happened?? I can only hope Jan was the result of some wonderful but ill-timed romance. The alternative is too dreadful. Whatever happened, Jan is my great-great-grandfather. Eventually, he named his daughter Willempje, likely in honor of his mum. She became my great-grandmother.

Strange how quickly people’s lives fade into oblivion. These people lived their lives, then died. And their stories? What happens to their stories? Maybe a few facts or memories get preserved, but what of all the sorrows and thoughts and day-to-day experiences? From Ancestry.com, I can piece together a few basics, but so much remains blank. Like those blackout poems, where you take a sheet of text and black out all but a few words in order to create a poem from the remainders.

What do the poems of my ancestors mean?

Ron and I are about to take our adult children and their spouses to the Netherlands. I suppose you could call it an ancestry tour, but I’ve been a very haphazard family researcher. Anyway, I’m only half Dutch, through my mother’s side. And what little I know about my family line is almost all new, pieced together through Ancestry.com and internet sleuthing.

My parents told me very little. As children of immigrants, born in the 1920s, my parents were not especially interested in “heritage.” Three of my four grandparents were dead before I was born. The fourth—Jan Hoogvliet’s granddaughter, my grandmother Maria—had succumbed to benign dementia by the time I knew her, and she died when I was twelve. I knew my mother’s six older siblings and my much-older-than-me cousins, a little. I never met my father’s two sisters or their families. Ever. They were never spoken of. (Turns out his ancestry is rather interesting after all, as we discovered in 2019.)

So, as I’ve written before, I’ve always felt a little “unmoored,” as if my family appeared rather out of nowhere. Sure, we were embedded in a Dutch enclave, and serious about the heritage of piety. That we cared about. But we were Americans, concerned with the American dream.

I wonder, then, what I’ll feel when we arrive in Kapelle, Zeeland, or Strijen, South Holland? Some sort of tingly sense of recognition? Will the landscapes and seascapes of these regions awaken some deep, ancestral memory? From what I can tell, “my people” lived and died in the Kapelle (grandfather) and Strijen (grandmother) regions going back at least to the 1600s. They were not an adventurous bunch, I guess. Which might help explain why I am such a homebody myself. Travel makes me very anxious, honestly.

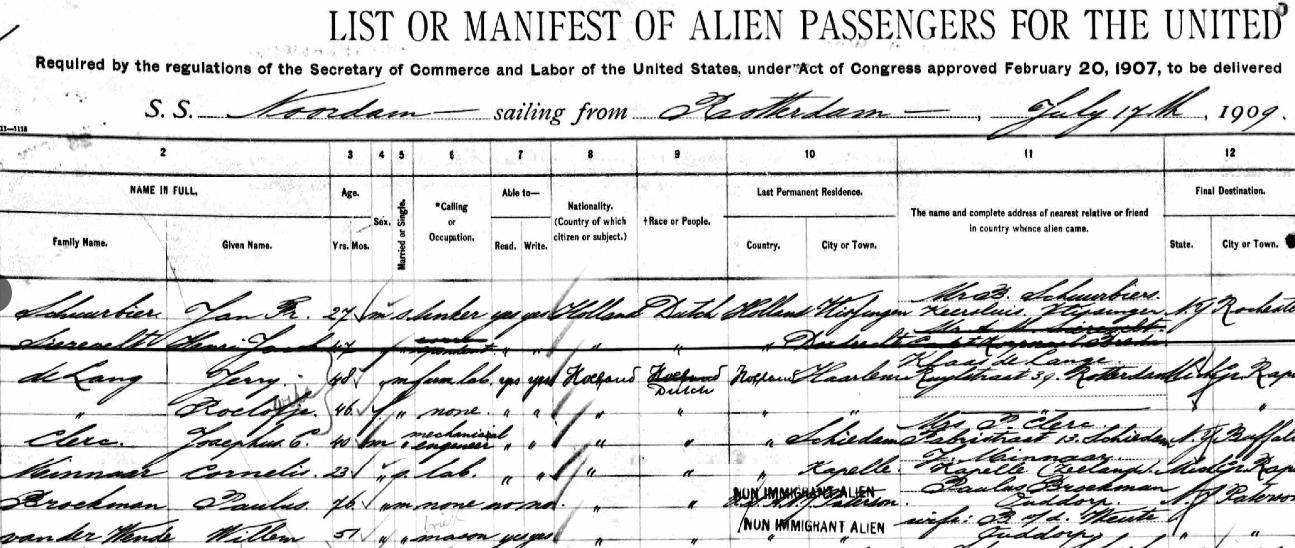

Imagine what it must have meant for my grandmother, orphaned by age 13, to emigrate to America with two brothers. Or my grandfather, age 23, to step onto that boat (the Noordam, out of Rotterdam, in July 1909), and leave father, brothers, and generations of roots behind. Cornelius and Maria met in Grand Rapids (I don’t know how. At church?), married in 1914, had seven kids—all after Maria turned 33, my gosh, woman! Their youngest child was my mother.

My mother eventually had me, and I grew up and married a guy whose entire family line is from… Friesland. Also going back along all the branches to the 1600s at least. We’ll be visiting Friesland as well on our little family adventure. Apparently, there is a tiny, tiny town called Rien, just southwest of Leeuwarden. Of course, we will make a stop.

I wish I were more prepared for this trip. I wish I had many, many more hours of research under my belt and a tidy, organized narrative to share with our kids. But I’ve had to do this work in snitches and snatches, and we’re left with a still-patchy picture. It’s been fun, though, to uncover even those little patches of the past.

The Strijen census from 1880-1890, showing the Roos family. Maria (my grandmother) and brother Willem Roos were eventually crossed out when they left for America in 1897. The mother and younger brother were crossed out when they died. (Teunis died in 1893; not sure why his name is still there.)

Some of what you can uncover proves rather amusing. For instance, in Ron’s family, there were five generations during what must have been some kind of tragic name-famine, because the family kept naming sons Gerben or Klaas or Gerben or Claas (or Claes), alternating across generations. No other ideas, people? I suppose that’s just what one did.

I’ve discovered serious things, too. Thanks to Dutch census records, for instance, I learned that my grandfather, two years after his mother died when he was 19, left Kapelle. The census record says that on February 27, 1907, he went to “Loosduinen (gesticht Bloemendaal).” What’s that? It was a Christian mental hospital near The Hague. It was run for many decades by the Dutch equivalent of the Christian Reformed church. Cornelius, what happened, honey?

I may never know. I’ve had some very nice correspondence with Dutch officials, who pointed me to a digital archive of patient records from that hospital during that period. I can see the records online. They’re handwritten, they include photos. They’re fascinating, even though I don’t read Dutch except with Google translate. However, the records are fragmentary, and I didn’t find my grandfather’s records. I am guessing he was admitted for “melancholia.” In any case, by 1909, he was on a boat to America.

The sleuthing requires patience and resourcefulness (and good advice—thank you, Janet Sheeres!). And when you actually find something you’re looking for, it is rather magical. I think this is mostly because the past is such a mystery, for all of us, and we are naturally fascinated with other people’s lives. The people I’m researching are connected to me, so I research them rather than others. Yet I feel no particular pride nor shame in my ancestors—just… curiosity. Everyone’s ancestors are interesting, just because they were human and they lived in this world.

The ordinary people in my little family tree lived their lives, in daily detail, from birth to death, embedded in moments of history that more or less influenced their choices. I catch only the tiniest glimpses. I know nothing about their workdays, what they liked to cook and eat, how they felt about their friends, what kind of advice they gave or received, what they said when they were angry, how they worried about their children, or how they prayed. I wonder about the prayers these people prayed.

Even after assembling a bunch of birth and death dates and visiting “ancestral” places, I will never be able to tell these people’s stories. The poetry of their lives will remain, at least to me, mostly dark. I do feel a kind of melancholy about that. I suppose, in a way, the remnants of their lives get woven into my own poem, for now.