I have loved Roz Chast’s cartoons since one of my college friends introduced me back in the 1980s to Chast’s quietly twisted portrayals of ordinary neuroses and domestic absurdities. Chast specializes in boring people, living room couches, potted plants—yet somehow she cuts life on the bias and makes thought-provoking curlicues out of the clippings. A typical cartoon: a glum-looking guy standing in a room, with the caption: “Never the experiment. Always the control.” Or a series of frames under the heading “Lifetime Achievement Awards,” containing figures with captions like “Recognized for never missing a 6-month dental checkup since 1948.”

Chast has established a long and successful career on the foundation of the standalone cartoon format—a remarkable achievement. Publishing her cartoons mainly in The New Yorker since 1978, her odometer for that publication alone reads over 1200 cartoons. All those years spent reducing—as she might put it—“human fads and foibles” down to their cartoonish essence prepared her perhaps better than most prose authors for that most difficult of challenges: the memoir.

Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant is a graphic memoir about a topic highly resistant to humor: the decline and death of elderly parents. Chast details the last difficult chapters of her parents’ lives, a period during which she had to grapple not only with the bewildering challenges of elder care but also with a deep love for her parents streaked to the core with exasperation and hurt. Her story reads at once as entirely particular and startlingly universal.

The main narrative begins in 2001, when her parents are already 89 years old and can no longer make the trip to visit Chast and her family in Connecticut. So the daughter returns for the first time in over a decade to her parents’ apartment in Brooklyn, the same apartment where she grew up and which she hated even as a child. We follow in detail the parents’ decline in their home, Chast’s difficulties moving them to assisted living, and their last illnesses and deaths.

I flew through this book, not only because one can read pretty fast with all those pictures, or because I have reached the daughter-caregiver stage myself and thus can “relate,” but mostly because I was amazed anew at the deeply affecting power of the graphic narrative medium: to convey character concisely, to arrange materials effectively, and to modulate tone.

Chast spares nothing in her truthful depiction of her parents, both born in 1912 to Russian immigrants whose cups of suffering overflowed. Her father taught high school French and Spanish and her mother was an elementary school assistant principal, and both displayed the typical frugality and hoarding instincts of their generation. With just a few panels, some characteristic phrases, and several page-long episodes (as when Chast unearths a disgusting, forty-year-old oven mitt, and Mom comments: “Why waste your money? That one still works.”), we are quickly immersed in this world and we know these people. Dad, with his food neuroses, chronic anxiety, and gentle demeanor. Mom, who bosses everyone around, is always right, and, when crossed, delivers a “blast from Chast!” These two entirely dependent on each other: “Codependent? Of course we’re codependent!” “Thank God!”

As Chast portrays situations that anyone with older parents can recognize—a fall that leads to hospitalization, arguments over moving out of the home, agonizing decisions about facilities—she deftly interweaves the main narrative events with other material, timing the interludes to create emotional contour. We learn early on about her grandparents’ stories, for example, but Chast saves the bitterest truths about her own childhood until much later in the book. We only read about a series of terrible nannies and the depth of Chast’s childhood fear of her mother once her father has died and Chast is left to work through her anger and hurt as her mother’s life ebbs away.

During this sequence, as she recalls how she learned to cope with her mother’s dominating personality and angry outbursts, Chast draws a picture of herself as a child: “I learned to keep my head down…” the caption reads. In the next frame, the caption continues: “…and my thoughts to myself.” Beneath is a drawing of a book called “The Big Book of What I Really Think.” Behold the birth of the writer.

That Chast was able, all these years, to keep hold of what she really thinks is exactly what readers appreciate—because she’s able to say what we’re thinking, too. Most bracingly affecting to me in this memoir are Chast’s frank portrayals of her own inner turmoils. Early on, she depicts herself in total denial, cheerfully imagining that her parents would die in their sleep and she’d “never have to deal.” Much later, she admits that her beloved father, brought to stay at her house while her mother was in the hospital, drove her to the limit with his “chatterbox” tendencies, a result of his senile dementia. In several places, Chast puts real numbers on elder care costs, laments how her parents’ lifetime “scrimpings” are gushing away in “a Niagara Falls of expense at the end,” confesses to thinking about how this will mean less money left to her—and then hates herself for thinking that.

After a hospital stay, when Chast has at last reunited her parents back at their apartment, she inserts a self-depiction in which her own crazed face is surrounded by thought bubbles linked with arrows in a circle—to depict how she was going round and round with guilt and self-justification for leaving them alone and returning to her own family. No prose account could depict the hopeless guilt and desperate self-preservation of a caregiving daughter as simply and immediately as this cartoon. Another in the “Am I a bad daughter?” series.

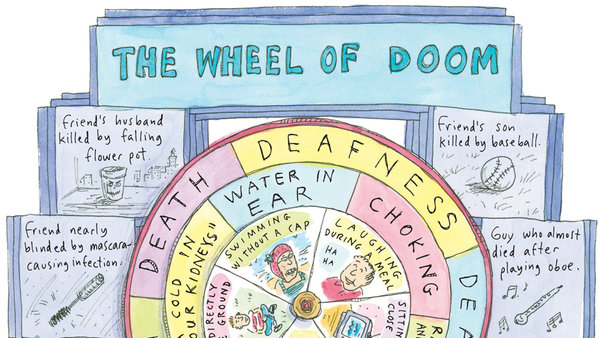

This all sounds very grim, but in fact the book is often funny, sometimes hilarious, as Chast uses cartoon techniques to zip momentarily into absurdity or to follow a silly scenario to its end. Neatly summing up her parents’ hypochondria and paranoia, for example, is a single page entitled “The Wheel of Doom.” At the center are hazardous activities, such as sitting too close to the TV, and these are surrounded by a wheel of dire results, such as gangrene or choking, which are then surrounded by doom-ridden ends, mostly death, all surrounded by microtales of woe: “A lump, then dead.”

Chast manages to be use humor frequently while neither trivializing anyone’s pain nor lapsing into dark brooding. Instead, she masterfully deploys all her expressive tools to create the fitting tone for the moment. I felt a familiar sinking feeling when I turned the page to the chapter entitled “The Old Apartment” and realized that we had reached the point where Chast would—shudder—have to clean out the apartment where her parents had lived for forty-eight years. After a few pages of narrative with drawings, Chast switches to actual photos of junk-filled rooms and puzzling ancient artifacts. One photo is captioned “Why was there a drawer of jar lids?” Anyone who has been in Chast’s position will nod with recognition.

Chast handles the most difficult moments in this story with a lovely gentleness. She follows the moment of her father’s death with a page containing only a sweet photograph of herself as a child with him. The following two pages contain no drawings at all, only her characteristic hand lettering as she describes the next harrowing twenty-four hours with her just-widowed mother. The final pages of the book contain a dozen simple crosshatch drawings of her mother in her last hours, Chast’s familiar cartoon style set aside for the sake of a more somber artistic study.

Good memoirs should be honest, revealing, and full of engaging particulars. Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant fully delivers, but gains even greater power from Chast’s signature cartoon style, skillfully adapted to tell this story. Readers who love Chast’s eye for the absurd and her preoccupation with anxieties will find that meeting her parents in these pages explains a great deal. We get a detailed portrait of crazy, but an equally compelling story of love. Perhaps that’s what her fans have adored about Chast all along: beneath the wit and wackiness there has always been, at heart, a clear-eyed understanding of human weakness, met with an abiding compassion.