Ugh, the media. We complain about it, yet we’re addicted to it. We don’t trust it, yet we imbibe its nectars—and poisons. We all have our impressions about media, but what do we actually know about fake news, echo chambers, and how media affects our life together?

Earlier this week, I was lucky enough to hear a lecture on American media trends by my colleague, Jesse Holcomb. Jesse is Assistant Professor of Journalism and Communication at Calvin University. Before coming to us in 2017, Jesse served for ten years as Associate Director of Research at Pew Research. Thanks to his work studying journalism and the media with Pew and more recently on projects for the Gallup organization, Jesse knows his way around polling, data crunching, and trend spotting.

Jesse’s talk was called “Media and the 2020 Elections: Four Big Trends to Watch.” It may seem odd to emphasize seeking the facts about people’s opinions, but Jesse argued that public opinion polling about media can serve as both a window and a mirror: skillful opinion polling helps us understand what others think and helps us see how our views fit into the larger picture.

Trend 1: The partisan trust gap is widening.

No surprise there, but Jesse put our trust gap in a longer perspective. Gallup has data since the 1970s showing that trust in news media has been steadily declining over many decades. As a snapshot: in 1999, 55% of people said they trusted the news media, while in 2019 it was only 41%. Fun fact: trust in the news media hit a low in 2016 at 32%.

Those numbers are averages. Here’s the severe “trust gap” part. In 2019, of those who self-identify as Republicans, only 15% said they trust the media. Among those who self-identify as Democrats, the number was 69%. (Independents: 38%.)

You know what everyone agrees on? Everyone agrees that we disagree not just on policy issues but on facts. When people were asked whether Americans disagree on policy issues only or on policy issues as well as facts, 20% said we disagree on just policy, 78% on policy and facts.

Later in the evening, Jesse remarked that people don’t necessarily think journalists are deliberately trying to fool them, just that all journalists and media have a point of view—they’re “biased.” In any case, this research supports the grim fracturing of our republic we’ve all sensed: “Everything is viewed through a lens of partisanship.”

Trend 2: We live in a high-choice media environment.

No surprise there, either, but our divide shows some evidence of softness in the middle. We know that the emergence of the internet in the 1990s led to an explosion of media sources and “sources.” “Here comes everybody,” is how media people wryly describe that explosion.

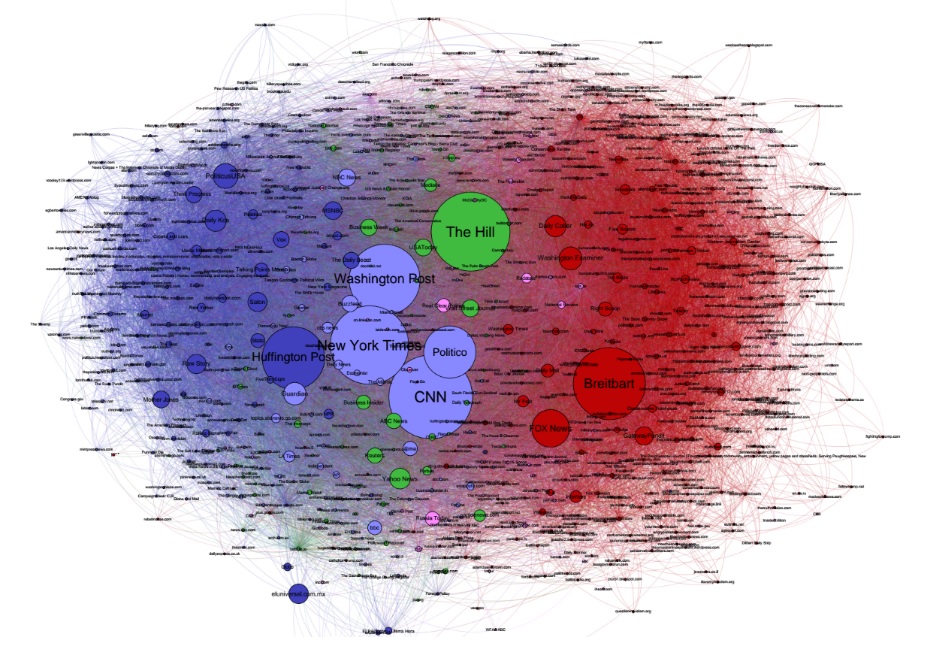

We also know that more news sources equals more audience fragmentation. Research shows that, indeed, as Jesse put it, “the strongest partisans live in alternate media universes.” In other words, the most liberal people and the most conservative people do not overlap at all in their news sources. Strong liberals get their news from CNN and NPR. Strong conservatives get their news from Fox and Hannity. The more moderate people, however, do overlap some.

It’s slightly encouraging, then, to know that not everyone lives in “filterbubbles” and “echo chambers,” in fact not even the majority of Americans. Only about 1 in 5 Democrats and Republicans live in news bubbles. Those who live there tend to speak loudly, that’s true. In our opinions and even in our lifestyle choices, the “big sort” is real. But apparently, when it comes to news sources, there’s a large muddly middle.

Trend 3: Misinformation is here, but it’s a wild card.

Fake news is not new. Even Russian troll farms are not new. Fortunately, research has not demonstrated that, currently, false information is bombarding us. Jesse reassured us that some excellent researchers are watching this phenomenon, and they are not seeing the “apocalyptic emergence” of fake news that we have come to fear.

However—and Jesse emphasized this point repeatedly—the fear is the problem. Our worry about fake news is more corrosive to our trust in media and in institutions than actual fake content has been. We wonder if we can trust anything we see.

Here’s some research. In 2016, 88% of people polled thought fake news had caused confusion about basic facts: 64% said a great deal of confusion, 24% said some confusion. Only about 1 in 5 knew that they had seen something fake. Puzzlingly, some of those said they shared the content anyway. Come on, people.

One of the more insidious recent trends is that, in battleground states (such as Michigan), we have to be on the lookout for “imposter content.” This is content generated by websites designed to look like local news sites, but which are actually operated by strident partisan entities. This is a cynical way of taking advantage of our lingering trust in local news. So keep an eye out.

Trend 4: The local news crisis is problematic for democracy.

This is perhaps the most important takeaway of the evening: we must rebuild local news ecosystems. I know this is a project central to Jesse’s research and dear to his heart, with good reason.

We know that local news media are in crisis. In the last twelve years, local newspaper advertising revenue is down 71% and the newspaper labor force is down 49%. About 20% of local newspapers have closed up shop. Yet, local news is the “workhorse” of media. Local news outlets make up 25% of all news outlets but create 60% of original content.

So what? Well, as Jesse put it, local news creation is “a prophylactic against misinformation.” Good local journalism creates “civic glue.” The presence of a strong local newspaper in a community, for example, leads to higher voting rates, more people feeling they understand the issues, and better accountability in local government. An “abundance of research” demonstrates that a strong local newspaper leads to better civic outcomes that both the right and left care about: responsive government, less corruption, less wasteful spending, greater civic participation.

“Our community information commons is at stake,” Jesse observed. And somehow we have to rebuild it. How?

Well, in the rest of the talk and in the Q&A period, we explored ways that people are experimenting with alternative funding models for news, including considering news organizations as “community assets” and thus funding them as we do symphonies and art museums, with a combination of donations, public funding, and subscription. A totally public funding model, such as the BBC, is a harder sell in the US.

We also discussed the technologies of news flow. Younger people, for instance, do not read papers or watch TV. They get their news on social media, using a “lean back” rather than a “lean in” approach—in other words, rather than looking for news, they figure anything important will find them in their feeds. People of all ages use various social media platforms to get news, and that raises the issue of algorithms, which tend to surface national news stories rather than local stories. No wonder our “head spaces” are filled with national stories and we know nothing about our own communities.

To get around that, we probably need to create news systems that bypass the big social media platforms. I found especially intriguing the example of the nonprofit group called City Bureau, which serves Chicago’s south and west sides by training ordinary people to cover local news. What if we were to raise up within our midst, in each community, a new generation of reporters?

At one point, an audience member asked about putting our current situation in historical perspective, and indeed, Jesse confirmed that in some ways, the present situation looks more like earlier, wilder periods of history. The golden age of newspapers from the mid-twentieth century, when papers and broadcast news sought to create “news for the interlocking public”—all that was based on a business model oriented toward getting the maximum number of eyes in front of ads. Thus, news organizations were incentivized to appeal to a broad reader- and viewership. This led to valorizing “voice of God” journalism, emphasizing objectivity and just the facts. That was, essentially, the agreement between the news producers and the public: journalists’ job is to be objective and thus they can be trusted.

To put it mildly, we’ve mostly emerged out of that era now. Even if the best journalists are still doing their utmost to be accurate and objective, a significant segment of the public does not trust them.

How to work past the mess we’re in and emerge toward a new era? I’ll let Jesse have the last word: “The best way to start repairing our democratic life together is right here in our neighborhoods. Local journalism has the best potential to cut through some of our partisan divides, to capitalize on the remaining trust that we have, and to create that civic glue to help us make informed decisions.”

Many thanks to Jesse Holcomb for permission to write about his lecture and for the image above. Image credit: Pew Research Center. Thanks also to the Calvin Alumni Association for sponsoring the event.