“A journey to the underworld is an epic convention,” I tell my world literature students on day two of class. Throughout the semester, we puzzle over these mythic journeys in every great text we read, from Gilgamesh to Paradise Lost. Sooner or later students start to notice versions of the underworld journey in contemporary movies and books, too. What draws us, we wonder, throughout centuries and across cultures, to the realms below?

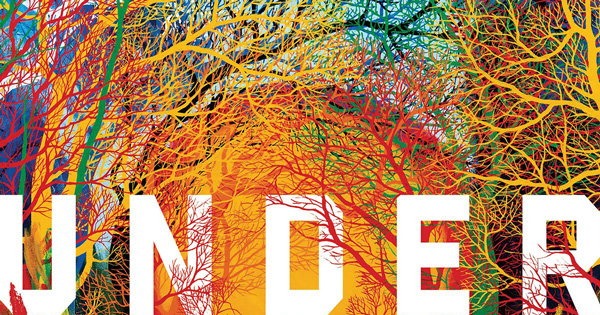

For me and my students, this exploration is entirely imaginative and literary, but Robert Macfarlane seeks to understand the mythical through the literal. Underland: A Deep Time Journey (released July 2019) recounts his adventures in some of the planet’s actual underworlds: caves, mines, forest soil, underground rivers, an urban substrate, a glacial moulin, a nuclear waste bunker.

Macfarlane’s journeys, remarkable as much for the philosophical and emotional strain as for the physical rigors they demanded, uncover what underlands mean to us: in these hidden worlds, we shelter what we treasure, dispose of what we fear, and coax the earth to yield what we desire. I found following Macfarlane’s journeys both arduous and compelling, yielding up the conclusion for me that the earth is a mysterious and uncanny place, and we don’t know the half of it.

Macfarlane is a startling combination of scholar, philosopher, poet, nature writer, adventurer. He is best known for his work as what we might call a geolinguist; he is a treasurer of words, especially regional landscape words, such as those catalogued in his book Landmarks. Reading his prose in Underland was thus exhilarating for its gorgeousness and variety of terms, always used for the purpose of exact precision. I had to look up over two dozen words as I read, including some real Scrabble treasures, such as zawn and quern.

Macfarlane’s formidable powers of description are put to the test in helping us imagine the eerie places he visits as well as his range of responses while in them. He conveys the claustrophobia he feels as he threads his way through a “ruckle”—a narrow passage of boulders in an underground cave system in Mendips, England—or squeezes through a body-hugging shaft under Paris. We feel his serenity as he swims a stone-cold lake in an underground chamber in Italy. We feel his exhaustion as he trudges through a storm on a days-long solo pilgrimage to Kollhellaren, a remote cave in Norway containing 3000-year-old cave paintings. And we understand his sobs when at last the paintings reveal themselves—ghostly red figures, dancing.

In each chapter, Macfarlane is guided by a fascinating cast of “Sybils” toward a distinctive encounter with the weird, with mystery, with “deep time.” In the underworld, time collapses as tens of thousands of years seem present at once in the rock and the darkness. There are good reasons why so many of the names to these underworld places have some version of the word hell in them. The underlands hide our horrors, as in the “war-machine” landscape of Slovenia, pocked with abandoned military tunnels and mass graves. And these places are typically extremely dangerous, a crossing of realms that offers numerous paths to death. But as ancient epics tell us, Macfarlane points out, “darkness might be a medium of vision” so that going downward can be a “movement toward revelation.”

In one of my favorite chapters, where Macfarlane and a mycologist called Merlin Sheldrake explore a forest near London, entering the soil below reveals the interrelatedness of the forest ecosystem. This is relatively new science, positing a “wood wide web” in which trees are connected underground by a mycorrhizal fungi network. Fungi have superpowers we are only beginning to understand, and they challenge our understanding of the biological world, busting up our carefully taxonomized categories and pointing to a mutualism beyond what we have previously perceived:

“All taxonomies crumble, but fungi leave many of our fundamental categories in ruin. Fungi thwart our usual senses of what is whole and singular, of what defines an organism, and of what descent or inheritance means. They do strange things to time, because it is not easy to say where a fungus ends or begins, when it is born or when it dies.”

This interconnectedness—among creatures and among epochs of time—is one key insight Macfarlane’s underworld journeys yield. Another is a paradox: human insignificance, human power. Contemplating the vast, blue-riven surface of a glacier in Greenland, in view of an ice cap and breaching whales, Macfarlane writes:

“The immensity and vibrancy of the ice are beyond anything I have encountered before. Seen in deep time—viewed even in the relatively shallow time since the last glaciation—the notion of human dominance over the planet seems greedy, delusory.”

For a moment, this sense of our insignificance is, for Macfarlane, a comforting thought. But then he remembers what he has also just seen: “the melt that is happening, that has happened, that is hastening.” Greenland is being transformed by the climate crisis. “The ice seems a ‘thing’ that is beyond our comprehension to know but within our capacity to destroy.”

Replace “ice” with “planet” and that sentence could be a fair summation of human relationship with the earth in the Anthropocene. The climate crisis is prompting a global reimagining of our role as humans. Those of us who are People of the Book like to look to Genesis 1-2 and talk about “caring for creation, serving and protecting.” We may have gotten past interpreting Genesis’s dominion mandate as permission for domination, but along with others I’m growing more and more skeptical not only about invoking any notion of “ruling the earth” but even about our usual, glib gestures toward “stewardship.”

As Macfarlane’s explorations affirm, humans have used our ingenuity to survive on this planet, to bend and use and manipulate its materials. We have filled and subdued and, in the last seventy years, we have at last achieved the ability to fully destroy this earth. So indeed, ruling the earth seems a preposterous prospect for human beings. We still do not have close to enough knowledge; we certainly do not have the spiritual capacities.

Well, what then? If we try to focus on Genesis 2:15’s “serve and protect,” what does that mean now that we have become world-destroyers? One answer comes in Macfarlane’s other two recent projects, Lost Words and Spell Songs. When Macfarlane noticed that words like acorn and kingfisher had been removed from the 2007 Oxford Junior Dictionary to be replaced by words like voicemail and broadband, he worried about what we are teaching our children to notice and know and care about. If we lose the words for ordinary birds and trees, how easy it is to lose the things themselves through our disregard.

So Macfarlane worked with artist Jackie Morris to create a lavish book of illustrated “spells”—playful, delightful poems that capture the essence of willows, bluebells, herons, and more, “summoning” them back into our consciousness through words and art.

The book—beautifully designed and produced in a huge cut size—has indeed turned out to have a kind of healing magic. It has “begun a grass-roots movement to re-wild childhood across Britain, Europe, and North America,” according to the Amazon page. In fact, people of all ages have embraced it. It has been used, for example, with Alzheimer’s patients, who trace their fingers over Morris’s ravishing, icon-like watercolors and suddenly speak lucidly of blackberry brambles in their childhood neighborhoods. People of all sorts and ages desperately long, it turns out, to repair our alienation from other creatures. Art is one way to begin doing that.

I’m so glad I invested in my own copy of Lost Words. Turning its pages, I found myself reading the poems out loud—I had to feel Macfarlane’s delicious lines in my mouth and ear: “Kingfisher: the colour-giver, fire-bringer, flame-flicker, river’s quiver.”

I’m also glad I invested in the companion book Spell Songs, with its accompanying CD (released July 2019). The songs are inspired by Lost Words and collaboratively composed by a group of mostly British folk artists. Musician Kerry Andrews wrote a response to the wren poem in Lost Words, then Caroline Slough of the Folk by the Oak Festival heard it, and the project sprung from there with the full participation of Macfarlane and Morris.

I listened to the songs while exploring the book—another beautifully produced work of art in itself, containing little essays by each musician, an interview with the artist, and several bonus poem/art “spells.” Everywhere in the book, there’s a strong push against anthropocentrism and an invitation instead to de-center ourselves and remember our kinship with the rest of creation. Each creature has its beauty and validity; our role is to respect and celebrate–through art, among other things.

Of the fourteen songs on the album, I especially love the Scottish folk song feel of “The Snow Hare,” the exuberance and longing of “Selkie-Boy” (about the gray seal), and the fluttery energy of “Willow.” The best songs are the ones that preserve but freely adapt Macfarlane’s words, enhancing their expressive power with melody and soundscape.

The final song, “The Lost Words Blessing,” is a heartbreaking lullaby calling us to “Walk through the world with care, my love/ And sing the things you see.” That seems to me a fully biblical calling, the one we most need to heed right now. Humans are ill equipped for so much in our relationship with the earth, but we are given the capacity for wonder, awe, and gratitude. We can love, we can bear witness.

Underland has won numerous “Best Book” awards for 2019. Teachers who are interested in using Lost Words or Spell Songs in the classroom will find many resources here and here.