Listen now

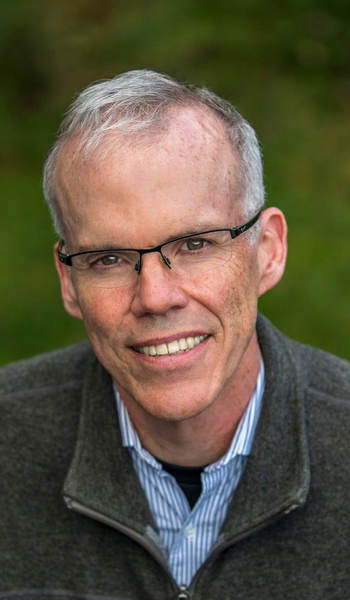

In this episode, we talk with climate activist and author Bill McKibben about an ethic of human solidarity, about activism, and about holding on to Christian faith. And we also manage to touch on the book of Job, the Milky Way, vernal pools, and, of course, refugia.

For more background

You can read more about Bill McKibben and his work at his website. His books include The End of Nature, Eaarth: Making Life on a Tough New Planet, and, most recently, Falter: Has the Human Game begun to Play Itself Out? Also check out the climate movement Bill helped found, 350.org.

Bill mentions a couple other activist organizations, including the Sunrise Movement and Extinction Rebellion.

Bill’s recent piece in The New Yorker about returning to church outdoors can be found here.

Transcript

Debra Rienstra: Refugia, a podcast about renewal. Refugia are places of shelter where life endures in times of crisis. From out of these small sanctuaries, life re-emerges, and the world is renewed. We’re exploring what it means for people of faith to be people of refugia. How can we create safe places of flourishing; micro-countercultures, where we gain strength and spiritual capacity to face the challenges ahead?

I’m Debra Rienstra, professor of English at Calvin University. And this is Refugia.

Bill McKibben: Even if we do everything right about climate change at this point, we’ve already bought ourselves enormous trouble. And so we’re going to need to be consciously building ways to help human beings cope with that, to cushion some of those blows.

Debra Rienstra: Hi, everyone. This episode is such a treat. Bill McKibben has lived and worked right inside the beating heart of the climate movement for over 30 years. He brings a bracingly practical, clear-eyed perspective on the past, present, and future of the climate crisis. But he does so with such generosity and warmth.

I caught Bill on a day when he was rejoicing in what he described as “the steady drip of good news.” Amid so much chaos and cynicism, Bill’s wisdom and persistence are an inspiration. Yet he consistently raises up others, especially intrepid leaders around the world organizing for change, many of them not even out of high school yet.

In this conversation I talk with Bill about an ethic of human solidarity, about activism, and about holding onto the Christian faith. And we also managed to touch on the book of Job, the Milky Way, vernal pools, and of course, refugia. I hope you come away from this conversation with renewed courage. I know I did.

Today I’m thrilled to be talking with Bill McKibben, one of the most important writers on the planet. I make that bold claim because Bill is the author of the foundational work for a general audience on the climate crisis, The End of Nature, published in 1989, and he has since written over a dozen other books about the climate crisis and related issues, including his most recent book, Falter. Bill is also a founder of the grassroots planet-wide climate action movement 350.org. Welcome!

Bill McKibben: Well, what a pleasure to be with you.

Debra Rienstra: Bill, your book Eaarth is one of the key books that changed the course of my life and got me involved in climate action. And you are also an incredibly generous person with your time and your energy, and I’m just so honored to talk with you today.

Bill McKibben: Well, it’s my pleasure. And, you know, writers really do love to know that their books have hit home every once in a while. So that’s very kind of you to say.

Debra Rienstra: Absolutely. Well, it’s true. I first met you when you were a featured speaker at the Festival of Faith and Writing at Calvin University in 2018. How have you been these past two years?

Bill McKibben: Well, the past two years have been, as you know, for all of us a strange and unprecedented stretch of time. That said, there’s some pretty good signs that have come through, even in the last year. A lot of the work that we’ve been doing around things like pipelines or divestment from fossil fuels and things have really kind of come to fruition. And I think that we’re better poised to make progress than we have been in a long time.

Debra Rienstra: It’s very exciting. Very exciting. What has sheltering in place been like for you? How are things in Vermont?

Bill McKibben: Well, I’ve had the easiest quarantine of anyone on the planet, I think. I live way out in the woods. As long as I can get out in the woods every day, it doesn’t feel to me like I’m hemmed in. And truthfully, there’s not that much lifestyle difference between being a freelance writer who lives deep in the woods and being in lockdown.

So I think I’ve had it easier than almost anyone. And so what I’ve been trying to do is highlight the stories of people who are having it very, very hard. I think it’s really important for people to understand that the same groups of people who are most affected by climate change and environmental pollution and, as it turns out, by police brutality and everything else are exactly the same people most affected by the coronavirus. So it’s really, really important, as we think about how we’re gonna change the world to deal with things like climate change, to understand that it’s not simply a matter of swapping out coal power for solar power. We’ve got to swap out what has been revealed evermore to be a really fundamentally unjust system for a much more fair world. And one of the levers for doing that’s going to be this transition to a working energy system.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. And I think more and more people have understood the power of systemic injustice because of COVID than ever before. It’s quite remarkable. And, as you’ve written, it remains to be seen how we’ll come out of this transition.

Bill McKibben: Well, I think that COVID teaches us two or three really important and interesting things. And some of them are about science. Look, it’s a very good reminder that physical reality is real. I’ve spent 30 years trying to convince people that physics and chemistry don’t negotiate, that you have to meet their terms.

And the COVID microbe is a strong reminder that the same thing applies to biology. Doesn’t make any difference if you don’t want to wear a mask; [if] the COVID microbe says wear a mask, then wear a mask. By the same token, the science is a reminder that speed is important. You know, the countries—I’m so struck, so constantly, by the reminder that the US and South Korea had their first coronavirus death on the same day in January. The South Koreans went right to work and did what needed to be doing and organized themselves and whatever.

And, of course, we did nothing. We have a buffoon in the White House. We twiddled our thumbs, got nowhere. And so yesterday, the state of Florida had more coronavirus cases in one day, in one state, than the country of South Korea has had in total from January till now.

Debra Rienstra: It is remarkable. And, you know, you, among many people, understand the power of denial. Human beings have this amazing power of denial. And, as you say, there are some things that happen that prove that reality is real, to say it in tautological terms.

Bill McKibben: Well, it’s true that human beings have that great power, but it’s interesting to look around the world and see that there are many places where it’s not as deep as it is here.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: And I think that that really goes to the third thing that we should learn from coronavirus, which is that human solidarity is really essential. You know, in our country above all others, we have spent the last 30 or 40 years in this grip of the idea that markets solve all problems.

You know, this kind of came from the Reagan era, and Reagan’s famous laugh line in all his speeches was “The nine scariest words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.'” It turns out those aren’t the scariest. The scariest words in the English language are “We’ve run out of ventilators,”‘ or “the hillside behind your house is on fire now,” and you can’t solve those by appealing to markets. Those you can solve if you can build efficient, effective governments and societies that get things done. We’re going to have to have that to deal with climate change. Clearly, the coronavirus is a reminder of what happens when you don’t have a working society, a working social sense of social solidarity.

Debra Rienstra: Right. You know, I think it’s fair to say that you have lived for many, many years every day with this heavy weight of knowing pretty much what there is to know in great detail about this historic moment of crisis convergence. COVID is just on top of these other crises we’re facing. How do you bear that weight day to day?

Bill McKibben: Well, truthfully, I think it’s probably an advantage at this point to have been working on this stuff for so long. You know, I wrote The End of Nature, which was the first book about climate change, when I was 28. And for a couple of years, it really was close to a kind of real depression.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: Time makes it easier, but really the only [antidote] to that kind of despair is engagement and action.

And it’s gotten paradoxically easier, the more that I’ve been able to figure out ways to kind of work to make effective change. So these last 15 years have been hard for other reasons—the kind of fierce counterattack from the fossil fuel industry that’s often come after me very personally and things. But that sense of despair has definitely lessened some, because it’s been powerful to watch these movements keep growing. 350.org was a kind of first iteration, a kind of beta test of whether you could build a climate movement. And nothing makes me happier than to see so many people flooding into this fight.

You know, in the last couple of years we’ve seen the Sunrise movement, which is mostly young people who’d worked on divestment in college and now have come up with the Green New Deal and are driving things forward. We’ve seen Extinction Rebellion, you know, really bringing nonviolent civil disobedience to new heights. And we’ve seen, most beautifully, the rise of young people all over the world. Greta Thunberg is magnificent. I’m so glad to have gotten to know her and be friends with her. But the best thing is to know that there are 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 Greta Thunbergs all over the world. Young people who are eloquent, powerful, committed, engaged. They’re great activists.

You know, I spent the fair part of last October writing college recommendations for people who I just think of as close colleagues in the climate fight.

Debra Rienstra: Fantastic.

Bill McKibben: So that’s—all of that cheers me up enormously.

Debra Rienstra: How do you celebrate good news, if you do?

Bill McKibben: Well, we celebrate by saying, how do we take this momentum into the next thing? But there are—one of the good things about some of these fights is that there [has] been a kind of steady drip of good news. The divestment battle’s really been the best example of that.

When we started it, you know, it was tiny. I remember the day that the very first institution divested—a small college in rural Maine, Unity College, with an endowment of $8 million. And I remember how out-of-our-skin excited we were at the news that someone had joined this fight.

Well, we’re at $14 trillion now in endowments and portfolios. It’s become the biggest corporate campaign of its kind in history. You know, in the last few months, the Pope and the Queen have both announced that they’re divesting their portfolios from fossil fuel. I mean, short of getting Beyoncé on board, I don’t know what we have left, but—

Debra Rienstra: She’s next. Don’t worry. She’s next.

Bill McKibben: Each day, there’s a new—some new institution now around the world, and each day, each bit of momentum just adds to itself, you know?

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: That’s the really good news, that these things just keep building and building.

And I think—and here’s, you know, I think, the powerful piece of what I hope is good news. I think that the work we’ve all done together over the last decade has now weakened the power of the fossil fuel industry to block change. When Donald Trump leaves office, the weakened position of the oil industry will be completely clear to everybody.

And I don’t think they’ll be able—as they have been for a decade, for three decades, really—to keep us from taking action. Now look, those wasted three decades that we wasted because they were running a huge disinformation campaign, those may turn out to have been the crucial three decades, and we may be so far behind the curve that we never catch up, but at least I think we’re going to have some chance to do the work we should have been doing all along.

And we’re poised to do it because, just as activists have been doing their job, so have the engineers. The price of a solar panel and the price of a wind turbine have dropped like a stone over the last decade. They cost a tenth of what they did in 2010. And so it’s no longer beyond the realm of possibility on any account that we could go and move quickly.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. I’m impressed with the people who are, despite everything that’s going on right now, working behind the scenes. I was just listening to a webinar from Ann Arbor. Ann Arbor has one of the most ambitious, if not the most ambitious, community carbon-neutral plans there is: A2ZERO, they call it. It’s impressive, these people who have been doing all this behind the scene, building coalitions and creating relationships of trust and centering equity and centering frontline populations just as you described a moment ago. It’s really impressive.

Bill McKibben: Amen. And watching those communities come to the fore of this fight has been crucial. You know, I’ve gotten to see it close up because I know who the people were who were working hard on things like the Keystone Pipeline a decade ago. And it was indigenous groups and Native Americans, farmers and ranchers, and, you know, people sort of had their eyes opened to that when we got to Standing Rock and the Dakota Access fight.

But it didn’t surprise me for a minute. I know that, not only in North America, but around the world, it’s indigenous people and frontline communities that have been at the forefront here. And how exciting to see that—

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: ‘Cause it really does allow for the possibility that the changes we’re going to make will be more than superficial, that we’ll clear the air of some of the carbon and some of the racism too.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah, it seems to me that it’s not a valid argument to say, “Well, we have to focus on racial justice, we don’t have time for climate change,” because both are happening at once.

Bill McKibben: Well, they’re not only both happening at once, they’re very much the same phenomenon in a lot of ways. I mean, think about what it was that George Floyd was saying: saying “I can’t breathe,” you know? Well, that’s right. You can’t breathe when someone’s kneeling on your neck. We know that that you can’t really breathe in a community that’s subject to police brutality. Things like hypertension are through the roof there.

You also can’t breathe when there’s a coal-fired power plant in your neighborhood, which is pretty likely if you’re an African American or Latino American. Asthma rates for Black Americans are three times higher than for White Americans. And you can’t breathe when the temperature just gets too high.

I was talking with our colleagues in Delhi last week. It was 118 degrees Fahrenheit. And people were having to stay inside in their homes because of the coronavirus pandemic, and they don’t have air conditioning.

Debra Rienstra: Oh, goodness.

Bill McKibben: Try to imagine what that feels like, you know? So this is the same fight, and we don’t know if we’ll win it, but for the moment, the important thing is that the fight is on, that there are people engaging it from every side, and that should give us some real strength.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. Let’s talk a little bit about faith. You’re a person of faith. Have you found yourself adjusting your spiritual life, so to speak, in the past several years, particularly since 2016? You’ve mentioned all these “triumphs against overwhelming odds” as you put it, but there’s also been kind of this daily trauma and chaos. And I just wonder if you have done anything in your own spiritual life to adjust to that.

Bill McKibben: Well, it’s a really important question. One of the worst things—I mean, from my point of view you could sit and list terrible things about Donald Trump all day and never exhaust the list. He’s a uniquely—I mean, it’s interesting, I work a lot with young people and for presidents, they have an n of two, okay?

Debra Rienstra: Right.

Bill McKibben: They know that Trump is a lot worse than Obama, but they don’t understand that he’s different from any other person we’ve ever had in this thing. Well, one of the things on that list, along with all the corruption and, you know, all the racism and all the, uh, you know—one of the things that really is distinctive about him is he never for a minute lets you forget about him.

And that’s terrible in so many ways, including just interfering with everybody’s mental health. I mean, look, I’m the worst meditator in the world to begin with. Like, my mind is pretty scattered and whatever to start with, but it’s hard to have—hard for me to have a kind of prayer life when your mind is constantly invaded by this kind of stuff.

So, one of the really interesting things about the coronavirus moment is for people to start realizing how much they really miss church, you know, just with the—I got to go to church last week for the first time, because we have a[n] outdoor—there’s a little campground, old Methodist campground near here.

And so they can have—when the weather gets warm, they can have church and outdoors in a[n] outdoor tabernacle and everybody in masks and everybody, you know, ten feet apart. And, you know, you don’t get to sing hymns, but at the very least, just to be there was quite wonderful.

Debra Rienstra: I read your beautiful piece on this experience, yeah.

Bill McKibben: You know, it wasn’t normal, but it shouldn’t be normal, and nothing should be normal. We’re in an abnormal time in an awful lot of ways, but that’s a moment to figure out what’s really important, you know?

Debra Rienstra: I miss the stability of weekly worship too. It’s often this moment of re-stabilization. And now, of all times, to be without that is really difficult.

Bill McKibben: I completely hear you. How has your daily—have you been able to kind of cope with the—just the kind of mental static and chaos over the last while?

Debra Rienstra: Uh, no. You know, I have my ups and downs, of course, and like you, I feel I’ve had it really very easy. I was on sabbatical last semester, so I didn’t even have to do what most of my colleagues had to do, which was pivot on a dime to online teaching. I didn’t even have to do that. I was reading and writing all day, so things didn’t change. But yeah, I was surprised, you know—you think, “oh, well we’re all stuck inside, I’m going to be so productive.” But that mental chaos is really difficult.

And, as you say, it interferes with your prayer concentration; your inner life is disrupted. So yeah, I mean, I’ve tried lots of different things. I wouldn’t say I’ve been consistent about anything. Although, I will say the psalms of imprecation have been extremely useful lately and extremely relevant.

Bill McKibben: It’s a good time to be reading Job too, I’ve gotta say.

Debra Rienstra: Yes, well, I want to ask you about that in a bit too. Are there theological ideas or biblical passages that you’ve found especially helpful in the past few years?

Bill McKibben: Job really is one of my favorite of all, maybe it’s my favorite part of the Hebrew Bible. And I’ve written about it some over the years, and this is a particularly good time to be reading it because what is it but a collection of trials and tribulations? And what does God do at the end of it but emerge to remind Job—really in what’s still a very radical thing to say—reminding Job that he’s not the center of everything. You know, that human beings are not actually the center of everything. And he sort of taunts Job and then takes him on a tour of the universe, all the animals and so on and so forth. And it’s extraordinarily comforting for me just to be reminded, when we’re in a period like this, that we’re not the only thing in the universe.

Debra Rienstra: That smallness can be comforting. And the terror and beauty of wildness— the way you write about this in your book on Job is really wonderful. But yeah, to put ourselves in that perspective. And I think that’s probably why so many people have been trotting out their front door into nature and watching birds. It’s just a small taste of what you’re describing is so important at the end of the book of Job.

Bill McKibben: The thing that I feel by far the most privileged about at the moment is that, because I chose to live my life out in the woods—I mean, you forego a certain number of things by doing that, but to always have access to that larger world. And, for me, to be able to go out at night and see a dark sky and really to be able to see the Milky Way every night is for some reason enormously comforting.

You know, I mean, it’s not—I’m not a kind of nihilist, saying, “Oh, well, you know, when our planet blows up, at least there’s a lot of other planets,” or something. That’s not at all how I think about it, but it is good.

I mean, what’s most disturbing about watching our president is the insane narcissism. That, like, everything in the world is about him. You know, like what happens? It’s about him. Which is, you know, not only unpresidential and inhuman and whatever, but—so to be able to just look through the telescope from the other end every once in a while and just be reminded that, in the end, not that much of it’s about Donald Trump or me or anybody else.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah, encountering this deep time has been extremely helpful to people too.

Bill McKibben: Nicely put.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

I wanted to ask you about this idea of refugia that I’ve been working on for some months now. And I wonder if that idea resonates with you. Are you familiar at all with the science of refugia?

Bill McKibben: Tell me what your—how you would describe it.

Debra Rienstra: Sure. So refugia are places where life can endure when there’s a crisis.

So, for example, if there’s a volcanic eruption [that] covers the mountain side with ash, but there are little pockets of life that endure and grow back, or perhaps it’s a wetland that doesn’t dry up completely so that plants and animals can survive there.

Bill McKibben: I think it’s a super powerful metaphor. I’ve always loved vernal pools, you know. Those places that aren’t there most of the year, but in the spring when it’s wet, they fill up in the woods. So there’ll be a little pond and suddenly out of nowhere there’ll be frogs, and they’re just there for a little while and then go into some kind of hibernation until it’s wet again. I think that that’s actually a terrifically good metaphor, your refugia one, for thinking about some of the ways we’re going to get through, well, the rest of this century.

There’s no way that we’re going to head off—even if we do everything right about climate change at this point, we’ve already bought ourselves enormous trouble. And so we’re going to need to be consciously building ways to help human beings cope with that, to cushion some of those blows. We’re going to need places—I mean, literally we’re going to need places where people and the rest of creation can gather to be out of the heat, you know, and away from the flood. And our physical world is shrinking. You know, the map of the planet—since humans first sort of wandered out of Africa, our world has been getting bigger and bigger and bigger, but now it’s getting smaller and smaller.

Debra Rienstra: Right.

Bill McKibben: And, you know, there’s a few billionaires who are quite hopeful of escaping to Mars, but for most of us, that’s not an issue, you know? And ways when I kind of hoped they would just, you know, get in there and leave the rest of us alone.

Debra Rienstra: We’ve had that conversation around my dinner table too, I’m afraid.

Bill McKibben: So, consciously thinking that way: mental refugias, but physical ones as well. One of the things I really want to be thinking about in the next few years is this question of how we cushion those blows we can no longer prevent.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: The UN estimates we could see hundreds of millions, up to a billion climate refugees in this century. And if we don’t do some thinking ahead about how that works, then we’re just going to see the same kind of xenophobic, racist sadness that helped split apart Western Europe, that turned many Americans into kind of cowards thinking that some invading army from the south was headed for them, or whatever.

I mean, there’s not enough walls and cages, even if that was the approach you were immoral enough to think was right. There’s not enough walls and cages to deal with, you know, a billion people on the move. We’re gonna have to enact some new ethic of human solidarity.

And it’s one of the reasons why I think that our religious traditions may be really important in this coming century, more so than we’ve kind of imagined they might be.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah, that was my next question, is what do you think it might mean for Christians to become, rather than people of empire, which has always been a temptation, I suppose for any faith, but instead of that to become people of refugia?

Bill McKibben: Well, I think that’s a really interesting—look, I come out of a Christian tradition that’s sort of dwindled the most, you know, kind of mainline Protestantism. I was baptized Presbyterian, grew up a Congregationalist and have been a Methodist my adult life just because of where I’ve been living. And none of these are traditions that are thriving in the ways that we measure, you know—how many people are going to church and things.

That said, I have a feeling that they may actually be poised to be important parts of the future, precisely because they’ve been broken down to the point where they’re no longer really part of the culture, the dominant culture, and that frees them to be part of a kind of counter to our culture.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. A refugia church.

Bill McKibben: Yes, precisely.

Debra Rienstra: I agree, and I’ve seen that in the UK. Very much so. My friends who are pastors in Scotland and England, they think of themselves as a church in decline, and they’ve sort of embraced that and discovered the freedoms in it.

Bill McKibben: Right. In this country, it’s been a little disguised because the rise of a kind of obnoxious evangelicalism—that’s what people came to associate with Christianity, and it was very hard to see past it because it was so noisy and whatever, but truthfully they’re in the same kind of numerical decline at this point, and for good reason, if you ask me.

And so I really do think we may be at a moment when, much to people’s surprise, these traditions begin to reassert some of their importance. Clearly, a kind of purely rational approach to the world hasn’t produced the kind of world that we really want, you know? We’ve been living in a political realm dominated by a kind of libertarian, corporatist impulse now for 40 years.

And, you know, so the temperature has gone up a couple of degrees and we’ve lost half the sea ice in the Arctic and on and on and on.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah, that plan’s not working.

Bill McKibben: Well, we may be open to some new ones, and that could be exciting.

Debra Rienstra: What I’m observing, too, is this sense of interfaith work on climate action, but also just building the capacity to work together as religious traditions has been also really hopeful.

Bill McKibben: Right. One of the things that people I think have come to understand is that there’s probably less difference between different religious traditions than between people who respond to any religious tradition and people who reject them. I actually have no problem with atheists and agnostics. I think that they’ve often had a clearer-eyed view of the world around us, and thank heaven for it.

But I think that where the interesting lines are being drawn actually is between people who aren’t religiously inclined and people who are religiously inclined, but in the kind of tolerant traditions of our various faiths, as opposed to the—you know, I mean, clearly one of the paramount dangers on this planet is a kind of intolerant and jingoistic faith of any kind, and it’s not just Christianity. I mean, take a trip to India right now and see what, you know, Hindu nationalism looks like, and it’s not any prettier.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. I mean, one of my theories is that the work of God right now is happening so much outside the church.

Bill McKibben: That’s a good way of putting it.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

I’m interested in how you might talk about scale. So, you think in planetary terms, I think, on most days, but you’re also deeply connected to your Vermont community, and you’ve written—at the end of the book Eaarth there’s some very persuasive sections about how we’re just gonna have to live a more limited, but maybe richer, life.

So, one of the puzzles I’m trying to think about is how refugia—which are, by definition, local, particular, small-scale, and they can even be temporary or transient, ephemeral—I’m trying to understand how that kind of locality and particularity can be helpful survival strategies when, ultimately what we need are these vast international and planet-scale transitions.

So, I guess the question here is, how do we connect the vast and the particular?

Bill McKibben: So, scale is the most interesting of all the questions and the one that’s most often neglected in a way, I think. And climate change does get at the paradox of them. I’ve done a lot of writing over the years about what I think is the need for far more localized economies and societies, mostly because—well, for all kinds of reasons, some of them environmental. But mostly because human beings are actually built to be in contact with each other, and we do best psychologically, morally, everywhere else when we’re living in communities that work and are intact. And it’s one of the reasons I treasure places like Vermont, where there is some of that.

On the other hand, we face the largest-scale problem we’ve ever faced. They don’t call it “global warming” for nothing. You can only solve it if you can figure out a way to act on a global level. And so that’s a tremendous paradox. One of the ways that we’ve tried to address it is kind of build this climate movement that’s able to work at both scales, you know? To have all kinds of people hard at work in their local communities, doing important things in their city, in their town, in their state, or in their nation.

Because those are where important decisions get made and so on and so forth, but also [to be] able to come together once in a while for big global demonstrations of our support. Those climate strikes last September, which drew 8 million people into the streets in the course of a couple of days last September, were a kind of reminder of how important it is that we show ourselves sometimes on that sort of global scale, even as much of the work that has to be done gets done close to home.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. And you’ve written, too, about the internet and [how] that has been such a powerful tool. I mean, even the Black Lives Matter movement has depended on the internet to do the connecting work. You know, maybe there’s these, what we might call refugia in local places, local communities, but that connecting work has to be done somehow, and the internet is a really powerful tool for that too.

Bill McKibben: Absolutely. I mean, look, the internet cuts all ways in our world. And, I mean, I think—if you press me, I think probably the world was better off without it than with it. I think that some of the habits of mind and heart that it’s encouraged are just—and I feel them in myself, the fragmentation of attention and so on.

But given that we have it, we best make use of it to do—I mean, what we’ve always tried to do when we—you know, like 350.org—was use the internet as a way to knit together face-to-face interactions. To get people out doing things in the real world, holding demonstrations. And then taking the kind of evidence of that, the pictures, and using the internet to share them around, to help people understand that they were a part of something big and plausible.

So one has to figure out how to use these tools as best one can. At the same time, you were asking before about mental health, and I’m afraid that things like Twitter have become barriers to actual mental health, too.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. Yeah, they can be little pools of anxiety-producing trouble. That’s for sure.

So, you have this incredible capacity to produce prose, for one thing. It’s remarkable. But also just to stay in the game year after year. How do you keep at it?

Bill McKibben: Well, I’ve been at it for a long time. I’ve just in the last few days announced that I was shifting my role yet again in certain ways. I’m going to turn 60 this year, and I’m gonna transition to emeritus status, mostly cause I’ve always viewed it as one of my roles is to try and keep raising up lots and lots of other people to kind of be in the forefront and be… So this will give me more time to help other people with the work they’re doing in lots of other organizations, and more time to think about some of these questions that we’re facing. And I find that really satisfying, to be able to help turn the spotlight on other people.

I do this weekly climate newsletter for The New Yorker. The part of it that I really treasure is—I’ve just called [it] “passing the mic,” where I every week find someone else to get to get across what they’re thinking at the moment, and that I really, really enjoy. It’s what I’ve been trying to do the last five or six years. I really have been stepping back a lot, and now in a more formal way.

Debra Rienstra: Yeah. I know that the title that you most prefer for yourself is ‘elder’. And that entails, you know, passing wisdom along and the kind of generosity that you display every day. So thank you for that work. And thank you so much for talking with me today. I really appreciate it.

Bill McKibben: It’s been a great pleasure. And I really think that this concept of refugia is awfully important. You know, I remember once talking with E. O. Wilson, who’s an old friend and a wonderful, wonderful human being. And just having him explain that something like 50 percent of the world’s remaining biological diversity was in two or three or four percent of the planet’s land mass, that there were places so important that we had to save them at all costs. And I think that that’s not only accurate and important, I also think it’s an important metaphor for thinking about how we guard our treasures. We’ve been careless—

Debra Rienstra: Yeah.

Bill McKibben: —in this world, careless in the physical world, careless in our mental and emotional worlds that we construct. And so it is time for some real care.

Debra Rienstra: Thanks so much.

This has been Refugia, a podcast about renewal. If you enjoyed this episode and you have a moment, please write a quick review on your podcast platform. Reviews help other listeners find us. You can find us on Facebook at Refugia Podcast. Leave us a comment and send us your ideas about what refugia means for you.

You can also visit our website at refugiapodcast.com. Explore links and transcripts from this and all our other episodes. You can find me on Facebook and Twitter at Debra K. Rienstra. Thanks for listening to the Refugia podcast.