The women who had come with Jesus from Galilee followed Joseph and saw the tomb and how his body was laid in it. Then they went home and prepared spices and perfumes. But they rested on the Sabbath in obedience to the commandment. Luke 23:55-56

Over the centuries, the church has put together some great liturgical moments for Holy Week. Maundy Thursday services commemorate that terrible evening of deepening darkness: the Last Supper, Jesus’ washing the disciples’ feet, the betrayal, Gethsemane, the arrest, Peter and the rooster—there’s quite a lot to cover. I’ve been to some very moving services over the years, services that created a tone of somber anticipation, repentance, and even a feeling of slowly advancing doom. Still, there’s a kind of almost-pleasure about entering this doom within the bounds of a service, among friends, singing quiet hymns and sharing the bread and wine. We are asked to meditate on the unwillingness of our spirits and the weakness of our flesh, but we know what’s coming and, in light of the Lord’s commandment to love, we do it together.

Good Friday services are similarly satisfying, as now in cold daylight we try to raise our faces and look at the cross. Maybe we don’t exactly enjoy reflecting on the torture and suffering of our Lord, but there we are, in our familiar sanctuary, listening to the seven last words and singing familiar songs about atonement and the love of Christ. We leave in reverent silence.

But then what? In most of our worship contexts today, the church gives us nothing particular to do until Sunday morning, when it’s all trumpets and lilies and pastel Easter frocks. Between Friday at 3 and Sunday at 10 (or 7 if you’re unlucky enough to face a sunrise service), you’re on your own.

From the solemn silence of the Friday service, we step out the church doors and go about our business. Let’s see: head to the grocery store for the Easter dinner items I forgot earlier. Then there’s laundry, a little TV, maybe on Saturday some errands and cleaning for the Easter guests. Kids go off to their part-time jobs or a friend’s house, maybe we grownups do a little office work at home. The devotional momentum we have been building since Palm Sunday tends to fade.

Certainly we don’t need church-directed rituals for every minute of Holy Week, but this do-it-yourself Saturday can have unfortunate consequences. Last year, my daughter’s Christian high school scheduled their “senior banquet” (i.e., prom) on Holy Saturday evening. We called the principal to complain about this, and the answer was, “Well, this was the only Saturday we could reserve the hall and caterer we wanted.”

“Yeah, you know why?” we replied. “Because every other school in town, including all the public schools, had enough respect for Easter observance to avoid this date.”

Some churches schedule an Easter Vigil service for Saturday evening, and these can be lovely. They begin outside, in darkness, with the congregation processing into the church with a single candle. A series of Scripture readings traces the sweep of redemption history. Sometimes there are baptisms, in keeping with an early church custom. The service ends in bright candlelight, Christmas-Eve style, with the first tentative stirrings of joyful Easter hymns. A good practice, but it kind of amounts to “Easter creep,” yes? Letting Easter creep into a pre-Easter day?

All right, then: what might a practice specific to Holy Saturday look like? Well, looking at our scriptural sources in the Gospels, we have two awkwardly opposite impulses at work.

On the one hand, we have the Sabbath. Why is there silence in the Gospel accounts about what happened between the burial of Jesus in Joseph’s tomb and the sunrise encounters? Because Saturday was the Sabbath. I find it impressive that the disciples persevered in observing the Sabbath. According to Luke, the women even had the presence of mind to get spices and perfumes ready before sunset Friday evening so they would be ready for Sunday morning. Practical, thinking ahead—good for them.

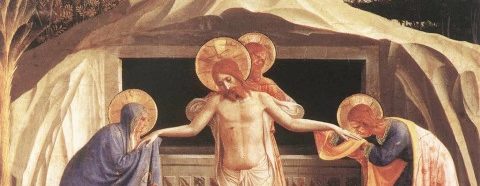

If we were to give Holy Saturday a sabbath feel, then, we might evoke the resonances of resting, dormancy, creation. “It is good,” said the Creator on the seventh day, and rested. “It is finished,” says Jesus, and rests. The work is done. The seed falls to the ground and lies dormant for a time. It is death, but in preparation for new life.

On the other hand, if we place ourselves in the position of the disciples, we remember that they did not walk away from the cross and tomb and return to business as usual. They were shattered and terrified. Maybe they observed the Sabbath the way we all cling to rituals when we simply do not know what else to do. They had no idea what would happen next. They stood at the edge of a dark abyss. “We had hoped,” begins Cleopas in Luke 24, explaining to the risen but hidden Lord why they were walking along, numb and grieving and heartbroken. Everything they hoped and longed for had been crushed by corrupt religious power, a lame betrayal, a farcical trial, and systematic, state-sponsored cruelty. I wonder if the disciples, amid their grief, turned toward anger and cynicism. “This is what happens to good people, to poor people, to our people: the forces of establishment and empire grind us up and never look back.”

So where do these twin impulses of sabbath and despair leave us on Holy Saturday? Well, I wouldn’t want to plan another church service for this day, mostly because I know what the vigors of Holy Week already do to pastors and worship planners.

The sabbath impulse suggests a time of quiet reflection, rest, dormancy—even amid Easter preparations. The Easter Vigil idea of reviewing redemption history seems fitting, too. Jesus comforts Cleopas and his companion on the road to Emmaus by showing from Scripture how the Messiah had to suffer, die, and rise again. Perhaps listening to portions of Handel’s Messiah would be a good means of redemption review. We associate the oratorio with Christmas, but that’s just part 1. Part 2 is the passion and resurrection and beginnings of the church, and it ends with the Hallelujah Chorus. (Maybe part 3 would be good Easter Sunday listening.)

As for the despair impulse, maybe Holy Saturday is an appropriate day to focus our prayer on all those who stand on the edge of an abyss. Even if we are personally not in a place of despair right now, plenty of people are, and maybe all of us have been or will be. So we could pray: for those who are still raw from the funeral, for those who are numb from abuse, for those who fear their government or police or military, for those in extreme poverty, for those succumbing to mental illness, for those who will never heal or get better, for those who are tired and cynical and angry, for those who just cannot see a good future, for all who feel hopeless. We can pray that when the morning comes, they will be given the faith to believe that something impossible has exploded their hopelessness into a new creation. We can pray that our communities of love will be gracious enough to embrace those in pain. We can pray that when the morning comes, our risen Lord will call each of our names.