Earlier this week, Steve Mathonnet-VanderWell sparked a lively conversation on this blog with his provocative question, “Does being a hard-nosed Calvinist who sees the struggle and brutality of nature make you a different sort of environmentalist?”

It’s a wonderful question. I rather like the idea of the Calvinist skeptic deflating overly romantic notions of nature’s wonder and beauty with nothing more than a single, withering glare. I suppose I’m displaying my Calvinist bonafides when I reveal that my favorite chapter of Pilgrim at Tinker Creek is the one in which Annie Dillard marvels at a world so designed that a good share of all creatures can only exist by “harassing, disfiguring, or totally destroying” other creatures. In fact, she observes, everything is nibbled, tattered, frayed, and infested with parasites. Praise the Lord!

Steve’s question places us, as he suggests, right at the nexus of wisdom and eschatology. Wisdom cites Psalm 104, where God provides water for wild donkeys and grass for cattle and wine to gladden the human heart. Lions, we note, roar for their prey, and God seems to revel in whipping up stormy weather. This is the earth, full of creatures, that God made in wisdom: there’s abundant provision, but also terror and death and returning to dust. That impressive admixture raises the question of eschatology: what is the end point of nature’s dependence on death to create life? Will lions and lambs someday lounge in vegetarian comfort together, and if so, would they still count as genuine lions and lambs?

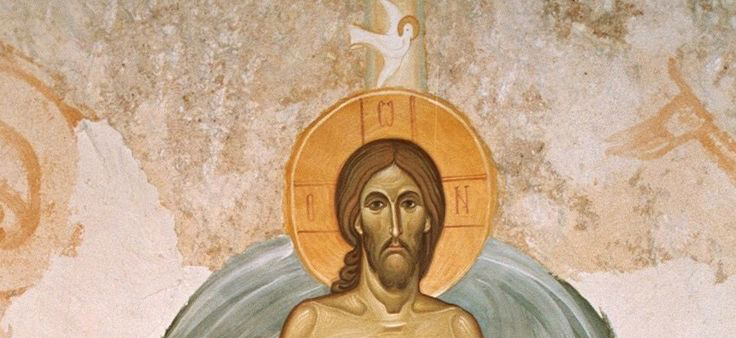

I honestly don’t know how to answer that question. However, I wonder if it might be useful to reflect on another nexus: the sacraments. The sacraments condense death and life into a single mystery, embodying this mystery in ordinary elements of the earth: water, grain, fruit. The sacraments thus shatter our temptation to divide the material from the spiritual, affirming the incarnational union of God and creation. The ordinary stuff of the physical world, the very fundamentals of survival provided by God, are transformed through human art and through the blessing of the Spirit, and they become means of grace.

Baptism takes water, the very basis for all life, and connects it to cleansing as well as to dying and rising. In baptism, we are cleansed and renewed, and we participate in the dying and rising of Christ. Communion takes bread and wine, products of ancient human arts derived from domesticated and cultivated plants, and connects these sustenance basics to remembrance of Christ’s death, our communion with one another, and hope for the eschatological banquet feast. These elements, as we call them, affirm our material embeddedness, gathering up along the way the entirety of God’s redemptive work: the fruit in the garden, Noah’s flood, manna in the wilderness, the life and death and resurrection of Christ, the river of life—all of it concentrated in ordinary things of the earth. God has chosen the simplest of things to become special means of grace so that we might see grace in the simplest of things.

In other words, as Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann wrote in his 1970 work For the Life of the World, the sacraments render the world transparent to God. Practiced regularly, the sacraments pull back the veil that makes the world opaque. Schmemann writes:

“The Eucharist is the sacrament of unity and the moment of truth: here we see the world in Christ, as it really is, and not from our particular and therefore limited and partial points of view. Intercession begins here, in the glory of the messianic banquet, and this is the only true beginning of the Church’s mission. It is when, ‘having put aside all earthly care,’ we seem to have left this world, that we, in fact, recover it in all its reality.”

The point of engaging in ritual actions—in setting aside some things as holy—is to train us to see the holy in all things. Over time, ideally, the sacraments work on us, teaching us that faith is more than words and ideas; through experience, sacramental practice trains us to perceive the whole creation imprinted with the presence and mercy of God, including the processes of death which propel the natural world.

Schmemann considered humans the priests of the world, as if the entire world was one giant eucharistic element and our job is to offer that world back to God as priests “of this cosmic sacrament.” I’m not sure, at this historical moment, that we need further elevation of human importance, since humans have never been more powerful and anthropocentric. But Schmemann is not the only theologian to emphasize our priestly role. Swiss theologian Jean-Jacques von Allmen—a Reformed fellow through and through—also posited the redemptive importance of human worship for the sake of the rest of creation. Not only do humans rediscover our “true life in worship,” we also discover our “solidarity with the whole of creation.”

I sometimes wonder whether the more-than-human creation praises God much better than we humans do. After all, blessedly free of all the stormy weather that self-consciousness inevitably brings to humans, creatures do not need the whole apparatus of religion to get them praising God. They do so simply by being what they are.

However, von Allmen thought that the rest of the world actually longs for us humans to engage in worship in order to complete the praise the whole earth longs to give. Because of the Fall, he writes, “the song of the world is now perceptible only as a sigh. But in [Christian worship], because there man has found again in Christ—the KEPHALE of the cosmos—his original function and ultimate end, the sighs and groans of creation can be transformed into singing.”

Creation cannot fully sing unless we worship well. That’s a lot of weight on us as worshipers, and a lot of weight on our sacramental practices. What happens if we neglect them?

Well, we’re finding out right now, not by our own fault. In these last months, deprived of in-person worship in the sanctuary, congregations have been making do with Zoom and Facebook. We’re worshiping as best we can, but it’s especially difficult to engage in sacramental practice, which depends on embodiment, depends on the gathered body of Christ in the flesh.

While I’ve missed everything about our Sunday gatherings, perhaps most of all I’ve missed our communion circles, where we gather around the table embraced by the voice of the congregation at song. We pass the bread and cup to each other and speak performative words: “The body of Christ broken for you. The blood of Christ, the cup of our salvation.” Sharing a cracker and sip with my spouse on the sofa at home has been, I’m afraid, a poor substitute.

Numerous stalwart and faithful people have confessed to me lately that their worship “attendance” has dwindled to rarely if at all. We are engaged in an involuntary experiment forcing us to ask the question: what is church for, anyway? Many people have been coping with pandemic restlessness by going outside, taking walks, finding God in nature. Do we even need church if we’ve got the woods and lakeshore?

It’s not that God isn’t present among the hills and trees and birds and clouds–general revelation and all that. But I would affirm that the church holds the means of grace through which that presence is fully revealed. We are people of Word and Sacrament. Both are essential. The sacraments are the ritual focal point where our cognitive understanding goes supra-rational and sinks into our bodies. The water, bread, and wine reveal Christ at the center of the cosmos so that we see Christ as the one in whom all things hold together. Lutheran theologian Paul Santmire writes: “the bread and the wine on the table are, for those eucharistic moments, positioned in the center of the cosmos, and the revelation of the divine energies of the crucified and risen cosmic Christ, in whom all things consist, radiates from that center”

In a few weeks we will observe Transfiguration Sunday. I wonder if transfiguration is not quite the right word. In that dazzling mountain-top moment, it’s not as if Christ changed before the very eyes of the disciples. It’s the very eyes of the disciples that were changed, so that they could perceive, for one intolerable moment, the glory of Christ. This Christ would soon gather even death into God’s redemptive purposes for all creation. The sacraments train us to pull back that veil, to taste and see, not only in worship but in every radiant ordinary lovely fearsome corner of creation, the glory of God.

Thanks to Ron Rienstra, my live-in supplier of von Allmen quotes and all manner of helpful theological processing.