“Taking Jesus’ body, the two of them wrapped it, with the spices, in strips of linen.” (John 20:25)

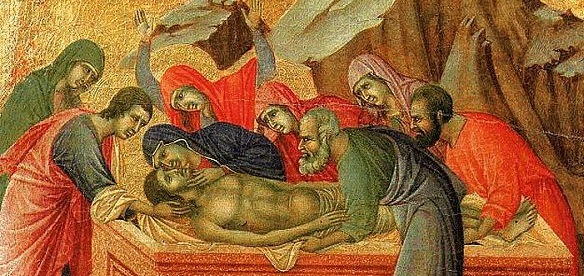

Joseph of Arimathea appears in all four gospels, but I am particularly drawn to the account in John, which includes some details beyond what the synoptics provide. Here Joseph is accompanied in his ministrations by Nicodemus—that other recorded member of the Secret Disciple Club. Nicodemus shows up with seventy-five pounds of myrrh and aloes, and the two of them together get the job done. We can imagine them, grim and hurried, managing the mangled body, one spreading the spices while the other pulls a fold of linen over and around. Perhaps on another occasion they would have had their own servants or a hired expert do this work, but I like to think of them glancing at the rapidly setting pre-Sabbath sun and agreeing, “Let’s just do it ourselves.”

Luke describes Joseph as “a member of the Council, a good and upright man, who had not consented to [the Council’s] decision and action” (23:50-51). Matthew mentions that he was rich (27:57). John says that Joseph “was a disciple of Jesus, but secretly because he feared the Jews” (19:38). John is the only one who notes Joseph’s discretion about his loyalty to Jesus, but if this is an offense, John seems to forgive it easily, perhaps exactly because Joseph rose to the occasion in this terrible hour. No one else could have done what Joseph did. Who among the terrified disciples or the women had the standing to dare a request to Pilate for the body of a crucified enemy of the state? Joseph must have known how to negotiate his way through the halls of power and make the ask. He also had the means with which to obtain the proper embalming materials and was able to secure rights to a nearby tomb, a new or at least never-used one, according to Matthew, Luke, and John. He, and let’s say Nicodemus and a couple servants, must have marched back out to that gruesome hill, right through the dispersing but still-gawking crowds, and talked the soldiers into taking the body down and handing it over. At this point, Catholic tradition allows us to imagine them pausing to allow a heart-broken mother a moment to embrace her son’s tortured body.

Once the body is buried, Joseph of Arimathea’s role in the official gospel accounts is over. But he has enjoyed an adventurous afterlife in the imagination of the faithful. In one early account, he is later imprisoned by the Jewish authorities, but the risen Lord appears to him, personally bathes him—in a lovely inversion of his service to Jesus—and frees him. In medieval traditions, Joseph manages to gain possession of the Holy Grail and, apparently feeling the urge to travel in his retirement (in some versions in the company of the Bethany sisters), he marches the Grail all the way to England—or perhaps it was his son who went. Accounts differ.

In any case, I wonder if traditional fascination with Joseph has something to do with our need to enter into the passion story. Each character in the story is a potential entry point in our devotional imaginations, but of course some figures are more inviting than others. We are often compelled by liturgy to enter the roles of Peter or Judas or Pilate or the angry crowd, and we do so reluctantly, with appropriate shame and guilt. The point of such exercises is to remind us that it was for our sins that he died. In fact, most of the big-name characters in this drama do not perform well. And the ones who do might make us hesitate: are we worthy to stand alongside Jesus’ mother or the beloved disciple?

So we look instead to those with bit parts, as it were: Simon of Cyrene; the women who “had followed Jesus from Galilee to care for his needs” (Matt. 27:55), all of whom seem to be named Mary; and then Joseph. Through these minor characters, who quietly step along the edges of the story, we witness the wonderful generosity of a God who not only suffers humiliation and death for our sake, but amid that suffering allows unimportant people to offer to his very person their tender, intimate gestures of mercy.

We often emphasize the loneliness of Jesus in the passion narrative. Yes, the Lord is a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief, betrayed, abandoned, defenseless, tortured, murdered. He could easily call down angels at any time; we have known that since the forty days in the desert. But he does not, because these terrible things have to happen so that the scripture will be fulfilled. Nevertheless, how beautiful that Jesus does allow a woman to wash his feet, an unwitting fellow to carry his cross, and two men of modest authority to wash and wrap his body. In two days, he will transform another woman, formerly possessed by demons, into the first evangelist of her resurrected Lord.

The beloved children’s show host Fred Rogers famously advised parents to comfort their children after a tragedy or disaster by inviting them to “look for the helpers.” The passion stories are full of villains, but when we look for the helpers, we find them. At this point, it would be obvious to ask how we might become Christian helpers, how we might imitate Joseph of Arimathea and Simon of Cyrene and the various Marys. And then we would arrive at the conclusion that we do so by “serving the least of these.” We minister to Christ by ministering to others in Christ’s name, especially the poor and broken.

That’s right of course. But I wonder about the state of extremity in which these helpers offered their gestures. Their actions had nothing to do with ambitious, kingdom-building missions guided by well-wrought vision statements and eager volunteers. As is true in modern-day tragedies, sometimes helpers are those who perform almost desperate actions out of heartbreak and bewilderment. Each of the helpers in the gospel accounts must have felt as if it was all too late and they were doing something pointless in total darkness. All their hopes for a new day had just been snuffed out. How do we enter the story through that?

Yesterday at the Good Friday service, we followed a liturgy based on the Orthodox “Akathist Hymn to the Divine Passion of Christ.” As we meditated on the burial, we prayed:

Grant us your grace, O Jesus our God. Receive us as you received Joseph and Nicodemus, that we may offer to you our souls like a clean shroud, may anoint your most pure body with the fragrant spices of virtue, and may have you in our hearts as in a tomb, as we cry: Alleluia!

Those ancients with their genius for allegorizing every detail! I love the idea of anointing Jesus’ body with fragrant spices of virtue. It struck me here and throughout the service that the prayers were inviting us to lift the actions of the characters out of the particular exigencies of the narrative and into a long history of Christian reflection. What Joseph and Nicodemus did hurriedly in darkness, we seek to do slowly, all our lives, in the light of the Resurrection.

We can only offer these ministrations because Jesus by grace deigns to receive them from us and indeed by grace supplies the means. We have no clean soul-shroud or fragrant virtue or new tomb to offer unless Jesus makes it so. Joseph provided a new tomb, cut from the rock. But Jesus himself must cut the rock of our hearts so that we might offer him a new tomb, a place where he might lay on this Holy Saturday, until on Easter morning no rock can contain all creation’s Alleluia.

One Response